The body of Rahma Lahmar, a 29-year-old

woman who disappeared four days earlier, was founded and it was

discovered that she was robbed, raped and finally slaughtered by a

30-year-old suspect who was arrested.

The brutality of this femicide

caused a wave of indignation in the country and many claimed for death

sentence, that it is provided by Tunisian legislation but which has not

been applied since 1991.

Demonstrations were also organized calling

for the death penalty for the rapist killer, widely approved by the

masses, while the president of the republic himself, riding the popular

wave, expressed himself in favor of this “solution”.

A

male-dominated, patriarchal society in which the dominant culture is

impregnated with retrograde and semi-feudal values relegates women to

the background, despite the regime propaganda elevating the Tunisian

woman by depicting her equal to men in republican rights and duties, in

reality this is only the latest in a long series of femicides and

violence and discrimination against women in the country.

Demonstrations

were also organized calling for the death penalty for the rapist

killer, widely approved by the masses, while the president of the

republic himself, riding the popular wave, expressed himself in favor of

this “solution”.

A male-dominated, patriarchal society in which the

dominant culture is impregnated with retrograde and semi-feudal values

relegates women to the background, despite the regime propaganda

elevating the Tunisian woman by depicting her equal to men in republican

rights and duties, in reality this is only the latest in a long series

of femicides and violence and discrimination against women in the

country.

The young Rahma like many other women

in the capital and in the coastal cities of the Tunisian Sahel, after a

day of work to return home is forced to walk a few kilometers along an

isolated highway to reach the nearest stop where you can take a bus or a

louage (collective taxi).

These objective conditions, which

add to the above, put a woman at a doubly risk not only of being robbed

but of suffering violence and even being murdered.

It is

understandable that in the eyes of the people rapists do not deserve to

live but it is also true that the popular masses must not be fooled that

the execution of such individuals solves the problem of violence

against women which is instead structural in this system.

Among the

few who have identified that the problem is structural and not merely

repressive, it was the Tunisian Coalition Against Death Penalty which,

in contrast with the climate of recent days, pointed the finger at the

responsibilities of state and government which in addition they do not

guarantee the safety of citizens, they do not solve economic and social

problems, contributing to the perpetuation of crime and widespread

violence that certainly do not fall from the sky. Through the mouth of

its president, Chokri Latif it was reiterated that death punishment, in a

bourgeois system where there is a class based justice, does not

represent a deterrent but a propaganda action by the power, spreading

illusions to the masses that the problem is being dealt with.

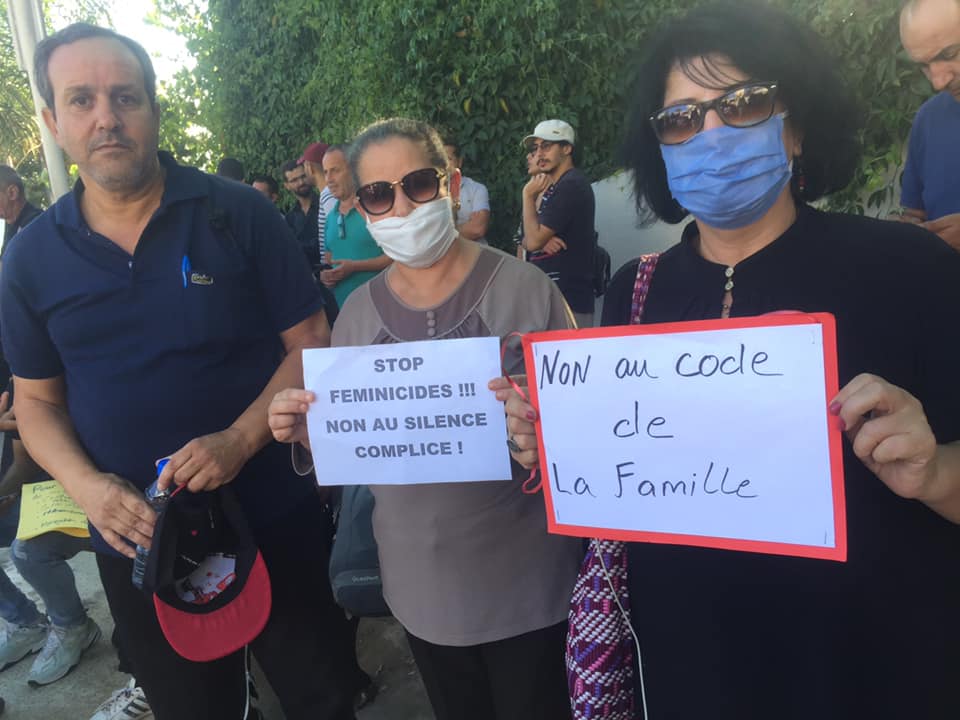

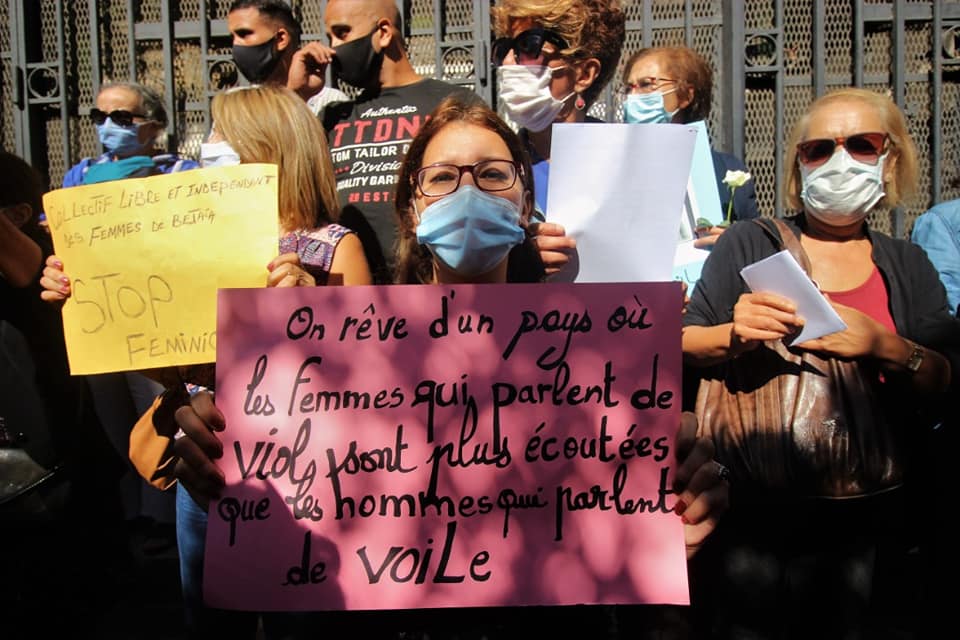

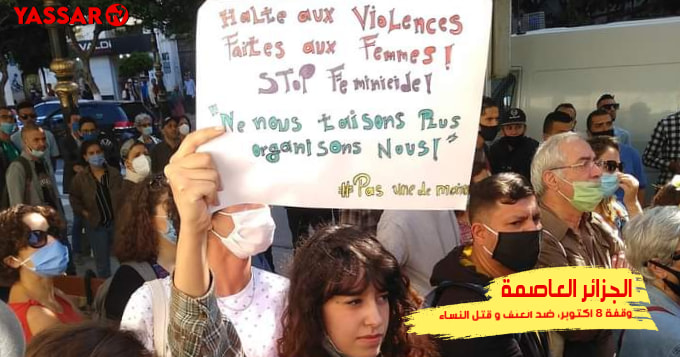

Also in Algeria in recent weeks there have been brutal femicides, there are 40 women killed since the beginning of the year, in a crescendo that takes the form of a real war against women of “low intensity”, the response of women and of the Algerian popular masses, however, was different from the small neighboring country.

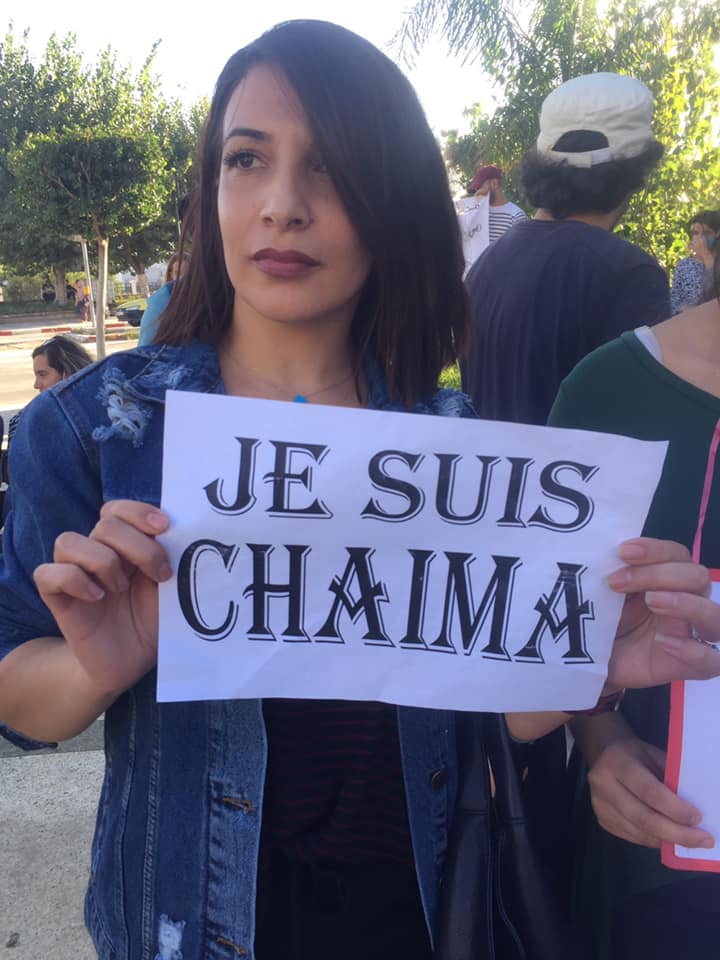

What prompted the mobilization was the

story of the young Chaima who in 2016 at the age of only 16 had been

raped and had denounced the rapist who had been sentenced to 3 years in

prison. Last October the 1st, the now free rapist approached Chaima

taking her to an isolated place in the city of Bou Merdes, and after

raping and killing her, he burned her body.

After a few days, on the

7th of October, another woman was found charred in a forest near the

city of Setif, an autopsy showed that she was burned alive.

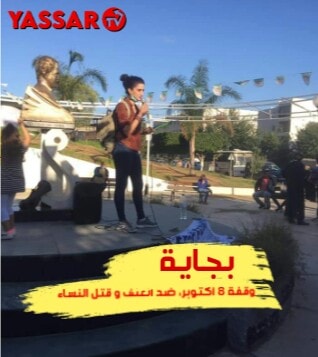

Algerian feminist collectives and women in general have organized demonstrations in several cities of the country and in particular in Algiers, in front of the headquarters of the University of Algiers (where the feminist movement often meets) in Bejaia (organized by the Collectif de Femme Libre de Bejaia), Oran, Costantine (organized by the Collectif de Femme de Constantine) and Tizi Ouzou.

The

sit in in Algiers was dispersed after 15 minutes by the forces of

repression of the reactionary Algerian military regime. This repression

is part of a vast repressive wave with dozens and dozens of militants

and demonstrators arrested in recent weeks but it is a clear signal that

the old reactionary power is an active part of the war against women

and that no justice is needed to expect from institutions.

The old

Algerian bureaucratic and comprador state took advantage of the pandemic

and the consequent “retreat home” of the great “movement (hirak)

against the system” to hit hard on the most active militants and

organizers of this popular and mass movement.

Yesterday Algerian feminist collectives in France demonstrated in Paris in front of the Algerian Embassy.

The Algerian feminist movement regained strength during the Hirak

(the demonstrations against the system or against the Algerian state

that had been underway for almost a year and that only the pandemic was

able to stop, at least temporarily) also waging an internal battle

within Hirak himself in some men who participated in the

demonstrations wanted to stifle this female activities by accusing women

“of wanting to divide the movement against the system, starting a

battle against men” there were also attacks in front of the University

of Algiers by male demonstrators against female ones.

But the

Algerian feminist movement, perhaps not surprisingly, has resisted

“internal” and external attacks and is the one that is best resisting

this repressive wave while maintaining the red thread of Hirak.

No comments:

Post a Comment