The Indian government under the Bharatiya Janata Party treats Kashmiri Muslims as Erewhonian criminals, aggressively turning their longstanding struggle and their pain of living in a conflicted state into terrorism and ‘crime’, while also repeatedly pathologising Kashmiri Muslims as terrorists. This is reflected in the violence unleashed by the Indian army on the common, dissenting people of Kashmir, mutilating their bodies, their faces with pellets to counter the tension that erupted in the wake of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani’s killing in July 2016.

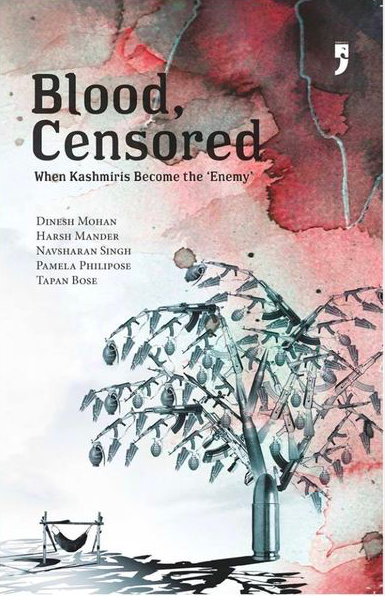

In December 2016, a team comprising well-known documentary filmmaker Tapan Bose, activist Harsh Mander, professor Dinesh Mohan, journalist Pamela Philipose, and independent researcher Navsharan Singh called the Concerned Citizens’ Collective travelled to Kashmir to assess the impact of the violence on the common and innocent people of the state. They brought out their findings in a book titled Blood, Censored: When Kashmiris Become the ‘Enemy’, published by Yoda Press in July 2018.

In the following essay, republished here with permission, the authors explain how the Indian Army, by openly filming and photographing the way they torture the Kashmiri ‘suspects’, in addition to the actual physical torture they inflict on them with the full sanction of the Indian state, has resulted in a violent visual culture that grants them greater and stronger impunity.

It is impossible to comprehend the policy of New Delhi with regard to Kashmir without recognising that for people on both sides of the ideological divide in India, Kashmir has a supreme symbolic importance well beyond just the land and its people. What makes Kashmir supremely significant for both is that it is the only Muslim majority state in India. All other Muslim majority regions in undivided India (except Hyderabad which was subdued) joined the union of Pakistan. Kashmir, through a historical default, remained with India.

For secular Indians, Kashmir is a test-case for a country that declares in its constitution that the nation belongs equally to people of every faith. By that tenet, the fact that Kashmir has an overwhelmingly Muslim population is irrelevant to the claims that Pakistan lays on Kashmir, on the grounds that the majority of its people are Muslim; because Pakistan is a country whose central organising principle is religion while for India it is not. The problem is of course the gaping chasm between the principle and practice of India’s constitutional secularism. If the majority of Muslims in Kashmir are not convinced that India in practice assures them the dignity and protection of equal citizenship, then the moral claims on their hearts and minds of India’s secular constitutional break down. They also shatter if the Hindu (and Sikh Buddhists) minorities do not feel safe and equal in Kashmir. The exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits from the valley in the 1990s, and the lack of any effective political and social initiative from the Muslim residents of Kashmir to either prevent their flight, or to ensure that they can return safely today and live in mixed settlements with their Muslim neighbours as in the past, further enfeebles the secular premise for Kashmir to remain a part of India.

But the greatest weakness for those who believe that Kashmir’s continuation in India is the ultimate litmus test of the success and authenticity of its secular credentials is that if the majority of Kashmiri Muslims demonstrably do not want to continue to throw their lot with India’s destiny, then no secular democratic principle is endorsed by holding them to India by decades of military suppression.

For the Hindu nationalists, on the other hand, precisely the fact that Kashmir is a Muslim majority state makes it suspect in its loyalty to the Indian nation. In the eyes of the RSS, in the orthodoxy of the Sangh, the Muslim is the ‘enemy within’. The taming and domestication of Kashmir has therefore always been high on the RSS agenda for India as a Hindu Rashtra, the flying of India’s flag in Lal Bagh central square in Srinagar. (The irony is that the RSS has long refused to fly in Indian tricolour in its headquarters in Nagpur; it flies instead of a saffron flag). The annulment of Article 370 of India’s constitution, which guarantees a special status to Kashmir, is one of the triumvirate of paramount demands of the RSS. The other two are the construction of a Ram Temple at the site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, and a uniform civil code (again aimed to revoke the rights of Muslim men to have more than one wife or to divorce their spouse at will).

Therefore, in the present era of triumphalism in the Hindutva camp, with Prime Minister Modi’s repeated impressive successes in the hustings, the suppression of any kind of popular or militant Kashmiri assertion is politically fundamental to the advance of the Hindu Rashtra. It is for this reason that the domestication of Kashmir is seen to be imperative not just for the integrity of the Indian nation, but for the triumph of Hindu nationalism.

Unlike in the erstwhile UPA administration, which also subscribed to a militarist approach to Kashmir but at the same time kept open other avenues of dialogue and development, the present administration is happy for the Kashmiri to see the Indian state mainly in the form of a menacing and unrelenting gun-toting Indian soldier.

The Guardian asks, ‘How did India get here? How is it all right for a constitutionally democratic and secular, modern nation to blind scores of civilians in a region it controls? Not an authoritarian state, not a crackpot dictatorship, not a rogue nation or warlord outside of legal and ethical commitments to international statuses, but a democratic country, a member of the comity of nations. How are India’s leaders, thinkers and its thundering televised custodians of public and private morality, all untroubled by the sight of a child whose heart has been penetrated by metal pellets? This is the kind of cruelty we expect from Assad’s Syria, not the world’s largest democracy.’ The answer can only be—India got here because of the triumph of majoritarian nationalism: its hubris, its spectacular want of compassion.

***

The suppression of Kashmir is now a made-for-television spectacle, designed to both whet and assuage bloodlust in the rising ranks of Hindu nationalists, who see themselves as by definition the only authentic Indian nationalists. The army records videos of its military operations and successes, not just against Pakistan but also Kashmir, and hands these out to television channels which obediently, uncritically and often with a shared triumphalism relay these, portraying the unruly Kashmiri not just as the disloyal ‘other’, but as the enemy. It is difficult to recall an occasion in the past in which the army chief in India has openly held out threats to a section of the country’s own civilians. General Bipin Rawat does so belligerently, aware that he is openly intimidating young citizens of his country and theirs. The army is a highly disciplined force, and its serving officers would not speak to and through the media unless they were authorised to do so. Again, we do not recall junior officers of the armed forces defending strategies such as the human shield aimed against Indian civilians in the way that Major Gogoi did on prime-time national television. As Apoorvanand observes, ‘That it did not shock us when Gogoi addressed the nation through the media after being decorated is a disturbing sign. Before him, and the current army chief, we do not remember any army officer addressing a press conference, not even after the Pakistan Army’s surrender in 1971, not after Operation Blue or the Kargil conflict. In all these, the army was the main actor. But it refrained from being seen as the director. It was always seen as following the civil authority. The present government is invoking nationalism to legitimise itself. It is trying to show it is the first government which backs the army. The latter is obliging by making the government’s nationalist agenda its own.’

Even more extraordinary is the release, presumably by Indian army sources of videos, that record their harsh coercive and violent action against protesting Kashmiris. Earlier we could have expected security forces to restrain any such public celebration of their breaking of the backs and spirits of unarmed civilians, because of service discipline, for fear of criticism by liberal opinion within and outside the country, and perhaps the sense that the violent repression of one’s citizens is not something to publicly celebrate in a democracy. But no longer. Instead, these videos are circulated as evidence of army valour, and of decisive action against the unruly and disloyal Kashmiri. Mohamad Junaid says that the ‘open-air theatre’ of violent repression was an essential part of the strategy of the Indian security forces in the first phase of militancy in the 1990s. During ‘crackdowns’ on Kashmiri urban neighbourhoods and villages, the Indian military would pick Kashmiri men and publicly beat and torture them. It was done in front of other Kashmiris, who were forced to gather in open spaces and watch. This served ‘as a warning but also as a psychological operation to break people’s will.’

But he feels that the current ‘visual politics’ of the display of army action on social media in Kashmir is different. First, he says, it helps serve the political objective of satisfying hyper-nationalist sentiment: ‘The military is matching in practice what the true desh-bhakts are asking for in their blood-curdling discourse. The videos are meant to bring the Indian nation out of the closet, and unabashedly embrace the hard reality of Indian rule in Kashmir.’

The distribution of these videos, he says further, is also to reassert a fragile masculinity against the deflation he feels has taken place since Burhan Wani’s killing and then on election day on 9 April 2017. ‘The Indian military has become inadequate to the task of keeping Kashmir subdued, or at least this is what it reads in its assessment of the desperate nationalist mood in India. It has responded with febrile displays of violence where it used to try to hide it. For long, only images of mangled bodies of dead militants were publicly displayed to assert Indian military’s masculinity. Now it is bodies of unarmed Kashmiri civilians, beatings of youths and women, the humiliation of children, and blasted houses in Kashmir.’

One can agree or disagree with Junaid’s harsh assessment, but the question remains. Why should the army post celebratory videos of its severe punitive action against civilians who are unarmed or armed at best with stones, often very young, and sometimes women and girls? Videos that establish that the way it treats citizens of the country is in brazen violation of human rights, the law of the land, and international law?

For retired army personnel, free from even the formality of army discipline, this is of course open season. A number of them rally their hyper-nationalist rage against the rebellious stone-pelting Kashmiri youth in noisy television studios. An Indian Army veteran, Major Manoj Arya, wrote an open letter to Burhan Wani. He describes him as ‘despicable’. ‘You could have been an engineer, a doctor, an archaeologist or a software programmer but your fate drew you to the seductive world of social media, with its instant celebrity hood and all encompassing fame. You posted pictures on the internet with your “brothers”, all you fine young Rambos holding assault rifles and radio sets. It was right out of Hollywood… The day you started with your social media blitzkrieg, you were a dead man. You encouraged young men of Kashmir to kill Indian soldiers, all from behind the safety of your Facebook account. Your female fan following was delirious. You were a social media rage… I wish we had met… (before killing you). And your parent’s son is dead. Dead from a 7.62mm full metal jacket round to the head.’

No comments:

Post a Comment