The

number of coal mine deaths in China declined by 13.1 percent last year

to stand at 333. It was the first time that China had recorded fewer

than 0.1 deaths per million tons of coal produced, officials at a national coal mine safety conference in Beijing reported.

The total number of accidents fell by just 0.9 percent to 224. The majority of these accidents involved less than ten fatalities, and officials noted that there had been no accidents involving more than 30 deaths for the last 25 months.

The last such accident occurred at the Baoma Mining Co. colliery in Inner Mongolia in December 2016. Thirty-two miners were killed in an explosion, while another 149, who were working underground at the time, managed to escape.

However, just a week before the national coal mine safety conference, a roof collapse at a coal mine in Shaanxi on 12 January killed 21 workers. Of the 87 miners working underground when the collapse occurred, 66 escaped.

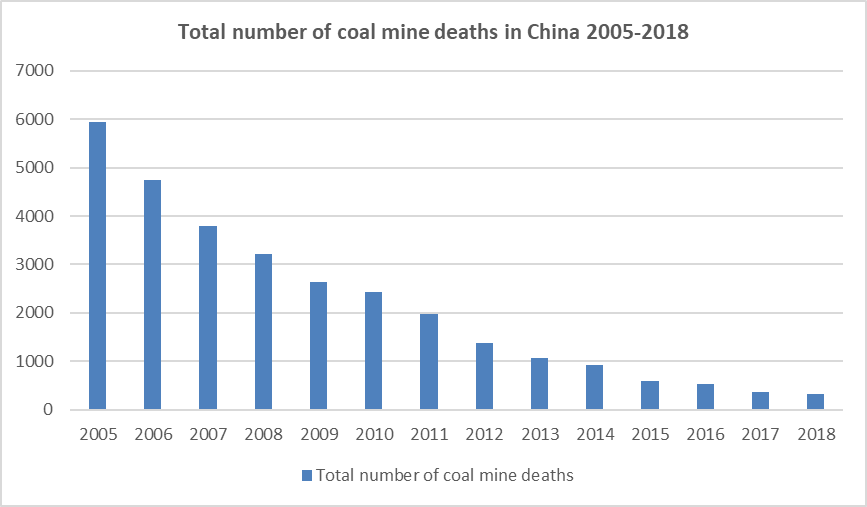

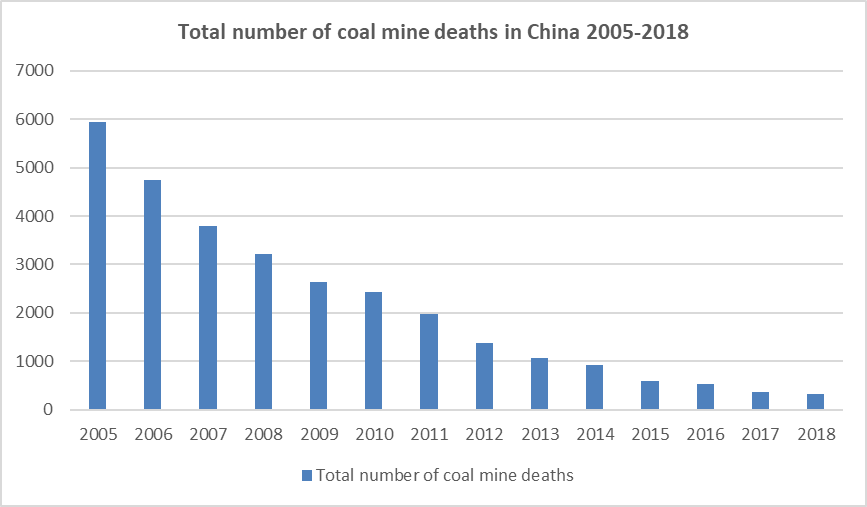

Death and accident rates in China’s coal industry have fallen consistently over the last two decades (see chart below). Several thousand miners died every year in the 2000s, when the industry’s rapid and largely unregulated expansion powered China’s economic boom. However, in the mid-2010s, demand for coal started to decrease, production levels fell and hundreds of thousands of miners were laid off.

In reality, the decline in accident and death rates in China has far more to do with mine closures and the falling demand for coal over the last five years than the introduction of any new safety measures.

There is always the danger that if the demand for domestic coal does pick up again, mine owners will seek to step up production or even open abandoned mines without taking the appropriate measures to ensure safety.

China Labour Bulletin has consistently advocated giving workers and the trade union a much greater role in the supervision and management of coal mine safety, and in particular giving workers’ representatives at the mine the power to demand a production shutdown when potentially fatal hazards are uncovered.

Government officials however plan to continue emphasizing coal mine inspections and mine consolidation as a means of improving safety. Officials reportedly inspected 159,000 mines last year, ordered 6,210 mines to halt production, cancelled the production licenses of 929 mining operations, and issued fines totalling 1.327 billion yuan.

However, inspections and fines rarely lead to an improvement in work safety. Government interventions are commonly seen by mine owners as an additional cost of doing business and do not inspire any meaningful change in the work safety culture at the mine.

The total number of accidents fell by just 0.9 percent to 224. The majority of these accidents involved less than ten fatalities, and officials noted that there had been no accidents involving more than 30 deaths for the last 25 months.

The last such accident occurred at the Baoma Mining Co. colliery in Inner Mongolia in December 2016. Thirty-two miners were killed in an explosion, while another 149, who were working underground at the time, managed to escape.

However, just a week before the national coal mine safety conference, a roof collapse at a coal mine in Shaanxi on 12 January killed 21 workers. Of the 87 miners working underground when the collapse occurred, 66 escaped.

Death and accident rates in China’s coal industry have fallen consistently over the last two decades (see chart below). Several thousand miners died every year in the 2000s, when the industry’s rapid and largely unregulated expansion powered China’s economic boom. However, in the mid-2010s, demand for coal started to decrease, production levels fell and hundreds of thousands of miners were laid off.

In reality, the decline in accident and death rates in China has far more to do with mine closures and the falling demand for coal over the last five years than the introduction of any new safety measures.

There is always the danger that if the demand for domestic coal does pick up again, mine owners will seek to step up production or even open abandoned mines without taking the appropriate measures to ensure safety.

China Labour Bulletin has consistently advocated giving workers and the trade union a much greater role in the supervision and management of coal mine safety, and in particular giving workers’ representatives at the mine the power to demand a production shutdown when potentially fatal hazards are uncovered.

Government officials however plan to continue emphasizing coal mine inspections and mine consolidation as a means of improving safety. Officials reportedly inspected 159,000 mines last year, ordered 6,210 mines to halt production, cancelled the production licenses of 929 mining operations, and issued fines totalling 1.327 billion yuan.

However, inspections and fines rarely lead to an improvement in work safety. Government interventions are commonly seen by mine owners as an additional cost of doing business and do not inspire any meaningful change in the work safety culture at the mine.

Section:

No comments:

Post a Comment